Strategic framing for optimisation

"No thanks, we're already optimised".

The polite refusal wasn’t the first, but this one surprised me more than others. The business in question had recently struggled against cost headwinds, underperformed compared to its peers and lacked a compelling long-term investment proposition. Operating performance fell short of aggressive budget targets. Morale in planning teams was low. What were once flagship operations were flagging, for want of a better word.

It begged the question, “Really? Optimised for what?” Unit costs? Cash flow? Long-term value? Short-term KPIs? Something else?

The long answer to this short question has three parts: 1) strategy, 2) planning ‘ethos’ and 3) systems and tools. Let’s consider what they might mean when planning an optimisation-centred transformation with a summary of each theme.

Theme 1 Strategy: Don't confuse slogans and juicy soundbites with strategy

The guidance and context given to planners were awash with management KPI’s and corporate aspirations. Phrases like “maximise productivity”, “reduce unit costs”, “extend production life”, “preserve optionality” and “increase reserves” popped up in presentations. A catchy slogan rallied employees around a ten-year target. But none of these flowed from a clear business strategy. Who directs what gets optimised, and how? And how would trade-offs be decided when objectives were conflicted?

In their 2005 paper, “Are you sure you have a strategy?”1, Don Hambrick and James Fredrickson called out these tensions:

“Without a strategy, time and resources are easily wasted on piecemeal, disparate activities; mid-level managers will fill the void with their own, often parochial, interpretations of what the business should be doing; and the result will be a potpourri of disjointed feeble initiatives”.

Does this seem familiar to those working across value chains and networked assets?

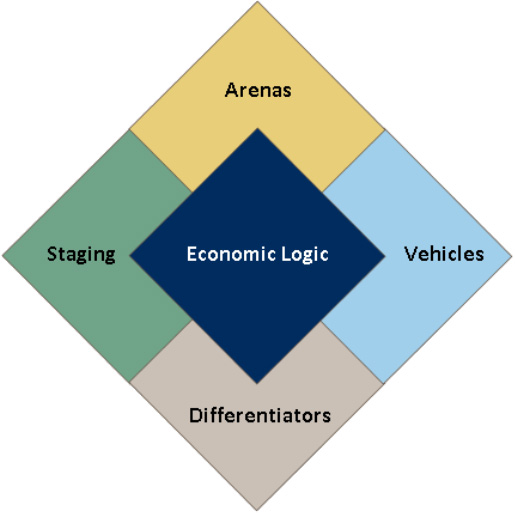

Hambrick & Fredrickson’s checklist for strategy has five focussing questions:

- Where will we be active (arenas)

- How will we get there? (vehicles)

- How will we win the marketplace? (differentiators)

- What will be our speed and sequence of moves? (staging)

- How will we obtain our returns? (economic logic)

Each decision node in the business had its own set of answers to these questions – their interpretation of what the business should be doing. Without a clear owner-driven strategic direction, informal versions and interpretations filled the void, each needing its own suite of plans. Planning teams were run ragged. A few months into the year, no one was sure which version of the plan they should follow.

Optimising across a value chain in these conditions is tricky. It’s even more complicated when its links are rusty or broken. But this shouldn’t stop us from moving forward with a digital transformation. The robust maths behind a good optimisation process will bring hidden problems to light and reveal where subordinate activities are gamed at the expense of the total system – the tail wagging the dog.

Theme 2 Planning: Optimisation based on optimism is sophisticated self-deception

Part 2 of the answer showed how top-down assumptions underpinned the objectives. Some of these targets were useful benchmarks, but others were founded on aspirational goals. Key parameters were factored in to fill the performance gap. In summary, optimism was programmed into the models. Optimisation built on optimism lends credibility to the most improbable of scenarios.

There’s another, perhaps better, word for this - Idealisation. Idealisation is a useful tool for breaking paradigms or measuring the gap between the theoretical and the practical. It’s also useful for feasibility studies on long-life development opportunities. But in the rubber-meets-road, dynamic world of operations planning and delivery, where humans are often overwhelmed by complexity and uncertainty, we want our optimisation tools to be sound and truthful. We want to begin with the data, not with the answer. To serve its purpose, the process must start being deductive rather than inductive, divergent rather than convergent, and bottom-up rather than top-down.

Theme 3 Systems & Tools: Software and engineering are how strategy is evaluated, not how it originates

The rest of the answer was a name-drop of software tools and systems. The brands and titles are familiar and well-regarded, and the competency and dedication of the users were not in question (the most significant asset in any mathematical transformation is still the strength of the team). But citing the number of cases, phases, shells or grids, the time spent crunching models, or any other proxy metric is no guarantee of optimality in the solution.

The French mathematician Henri Poincare described an aspect of this more than a century ago2.

“Mathematical work … is not merely a question of applying rules, of making the most combinations possible according to certain fixed laws. The combinations so obtained would be exceedingly numerous, useless and cumbersome. The true work of the inventor consists in choosing among these combinations so as to eliminate the useless ones or rather to avoid the trouble of making them, and the rules which must guide this choice are extremely fine and delicate.” (Henry Poincare, 1905)

Poincare’s ‘inventor’ is close to the role of strategic architect. Architecture is the precursor of engineering, connecting and interpreting vision, applying skill and imagination (invention) to produce a feasible design.

To sum up, strategy and the role of strategist is architectural. The role of strategic planner is to apply engineering, scientific and commercial rigour to the architectural design. Good mathematics enhances good strategy, but it won’t fix a poor strategy (although it can reveal where the flaws are).

Find the right sponsor

So, what does this mean when planning an enterprise-level optimisation?

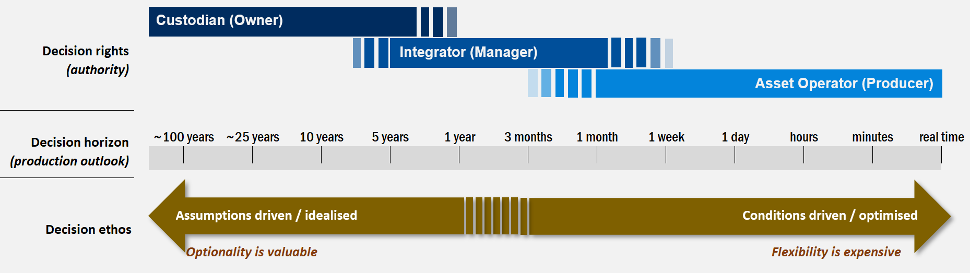

Let’s assume the business owner has a clear strategy in place that addresses each of Hambrick & Fredrickson’s five focussing questions. Firstly, see how the answers to these questions help define the scope and breadth of the process. Value drivers will be defined, the operating model will be clear, decision-making roles and authorities will be in place, performance measures will be matched to business performance, and so on.

See also how this process guides us in choosing the right internal sponsor for the program. This person will be senior enough to oversee the full span of activities and decisions within the scope. (Alternatively, it may be this role that approves the scope in the first place, for the same reason). Often it may not be a technical or operational role, even if the work itself seems to fit within these categories. Instead, it may be the CFO who is appointed since this role integrates planning, business performance and strategy.

We make this point because one observed mode of failure for otherwise successful optimisation programs is that the solution was sponsored and deployed at the wrong organisational level. One such example worked locally (exactly where the client wanted it to), but it introduced problems at the global level, which had the potential for a net negative business value outcome. The solution – elevate and broaden the scope to incorporate the big picture.

When we step back from discussing objective functions (the "what") and consider the purpose of our optimisation (the "why"), we move closer to the intent of the strategy.

'Occasionally optimised' means not optimised

“No thanks, we’re already optimised.” Another way of understanding that opening remark is in its historical context. It’s a carry-over from an earlier generation of software and computing power when a full life-of-asset strategic optimisation study took weeks or months to configure and execute. It also harks back to when the world was more stable and markets less volatile. In that context, optimisation was a task that was run once during project evaluation (usually pre-feasibility) and infrequently, if at all, between commencement and closure.

Times have changed. An entire life-of-mine, pit-to-port optimisation, with detailed design and full financials, can be run overnight. Ore Reserves could be updated for the market based on daily metal prices (just because we could doesn’t mean we should!). Dynamic mine planning can flex for real-world conditions (price, forex, weather, equipment performance, etc). Short-interval control with optimisation can rewire the production network in real-time in response to sensory data. In short, the new tools can do more than we’re currently asking them to.

And that means any business not taking advantage of these new capabilities stands a good chance of being outmanoeuvred and outplayed by competitors.

Making good planning great

The purpose of planning can sometimes get lost in the pursuit of top-down targets and aggressive performance metrics. That’s not to say there isn’t a place for aspirational goals (there is), but planning’s primary role is, to tell the truth to the business. “Bad news early”, as the saying goes. Early warning of coming trouble allows leaders to avoid or mitigate the hazard. In the same sense, “Good news early too” is just as important since it presents the business with an opportunity to capture extra value.

Good planners have always practised “what if” scenarios, rehearsing the decisions and actions they should take when the planning context changes suddenly and dramatically. With today’s advanced simulation and dynamic optimisation tools, planners are better equipped to measure and manage uncertainty across complex value chains and mining life cycles. And for leaders, the best way to lift the morale of dispirited planning teams is to equip them to succeed in their work, every time.

1 Donald C. Hambrick and James W. Fredrickson, 2005. ‘Are you sure you have a strategy?’ Academy of Management Executive, 2005, Vol. 19, No. 4

2 Poincaré, Henri, 1905. 'The Value of Science' (1958 paperback edition), translation by George Bruce Halsted, Dover Publications, New York.

Additional articles in this series include:

About the author

Rod Smith is the founding Principal of Beresford Advisory, a Brisbane-based resources sector consultancy focussed on supporting better decision making across the mineral value chain. He is a fellow of the Australian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy and a mining leader who was a part of Rio Tinto for over 30 years. During that time he held a variety of technical, operating and leadership roles, most recently as Chief Advisor of Planning & Scheduling. In that role he developed Rio Tinto’s Orebody Productivity framework and established its Operations Research & Decision Science group, building internal and external partnerships in the field of Industrial Mathematics to unlock significant value for the group.

To contact Rod Smith please email: rod@beresfordadvisory.com