Resilience in Mine Planning: Mindsets vs Toolkits

How should we respond when the unexpected happens in mining, as it frequently does? Successful planning teams react by saying, “We made plan despite…”, when others say, “We didn’t make plan because…”, and the list of reasons following each statement is identical.

As on the sports field, successful teams lift when the situation demands and opportunities present, but how do they do this? And what do they need?

In our first article, we introduced the concept of Defensive vs Offensive planning. We described a Defensive planning stance as one whose primary focus is defending the plan and budget, often despite a new reality unfolding in the real world. This type of plan usually emerges from a deterministic mindset and planning toolkit. For some planning horizons and operating conditions, there’s nothing particularly wrong or flawed with this approach. Under stable operating and market conditions survival/cost pressure drives diligence and discipline. Long term mine plans also fall into this category because they are built on long-run assumptions and are the foundation of the business investment.

However, from a risk and opportunity management point of view, the profile of a Defensive stance skews downward. Targets, reporting metrics and performance incentives reflect the business priority and drive behaviour. Heroes are made of those who scramble to deliver the numbers under trying circumstances. This is mining. This is what we do.

Is your plan built for comfort or performance?

It follows that the best plan creates alternate pathways to deliver the objective (usually the saleable production target at the budgeted unit cost). But optionality and flexibility, both valuable at the strategic planning level, are costly when carried to the point of plan implementation. Alternative mining areas, excess development, spare fleet and plant capacity, large stocks and inventories, and standby labour are luxuries only a lucky few can afford.

In the Defensive context, these options are like shock absorbers on a car – their purpose is to smooth the bumps on a rough road to give passengers a comfortable ride and protect the rest of the vehicle from damage. They are nice to have, but peak performance comes at the cost of a cushioning ride in racetrack competition.

If Defence is your dominant operating reality, advanced mathematical methods can assist by determining the optimal optionality needed to deliver the plan, cascading this from each business planning horizon to the next. For one large open pit coal operation with a lumpy coal production profile, carrying large ROM and product stocks was how the defensive schedule balanced grades and qualities across shipments. Optimisation with simulation discerned and predicted the conditions when stocks could be run low, keeping active watch over ship arrivals, weather conditions, maintenance schedules, grade control and production performance. The result was lower operating costs through reduced re-handle and less working capital.

To sum up, in a Defensive planning context, advanced maths will accurately match the level of optionality needed to deliver a plan based on the business's risk appetite.

So, what about the Offensive planning stance?

The saying goes in war and sport, “The best defence is a good offence.” In planning we say it a little differently, “The best offence begins with a good defence.” An Offensive stance begins with confidence in our planning processes and in our ability to execute the plan. From this strong foundation we look for opportunities to capture additional value in the market with a playbook that is poised to take advantage of these fleeting moments. On the flipside, if conditions change unfavourably, the business knows how to switch to stop-loss mode to mitigate or lessen the impact.

This is the difference with successful teams. Successful teams don’t just perform, in critical moments they outperform. That’s how winning performance shifts from occasional to habitual.

What does this planning stance look like in practice? Before looking at the technical, let’s look at the behavioural side. Firstly, it’s likely that the P&L of the business is a visible driver for operations leadership. The focus on safely delivering the plan remains in place, but the site is incentivised to find opportunities to outperform. To them, a lost opportunity counts as much or more than a missed target.

If there is margin in the market and capacity in logistics, this might mean contracting additional capacity to maximise cash flow, both through the bottleneck and around it. It could involve tolling or bypass, flexing cut-offs and product grades, trading activities and so on.

This leads to the second point: in its simplest form, time is the most important behaviour and value driver for capturing upside. This takes two forms, 1) the time it takes to identify and evaluate the opportunity and 2) the time taken to react and respond intelligently.

Press On or Park Up?

It makes sense then, that a plan which builds in opportunity to capture upside is also one that uses time as a value lever.

But here’s the problem. Calendar year production schedules and business plans assume the plan will be completed and delivered at midnight on New Year’s Eve. For a 24/7 operation this means every hour of the 8760 hours in the plan is accounted for before we even start the year. Any hour lost to an unplanned event is an hour lost from the year. It’s no wonder many mines spend their fourth quarter in a mad scramble for production tonnes, frantically raiding inventories and setting themselves up for a January hangover.

An Offensive planning stance uses time as that lever of stretch. As an example, an operation adopting this approach developed a milestone-driven schedule targeting completion of the budgeted plan by mid-December. By scheduling an early finish to the plan, the operation arrived in the fourth quarter with that most valuable commodity – optionality – in hand. If there was opportunity in the market and capacity to complete sales by the end of the month, the operation could press on by bringing production forward. If not, the operation could make a tactical stop to undertake maintenance, have employees take leave and ensure all is ready for an effective start to the next year. As it happened, the site was able to do some of each.

Takeaways

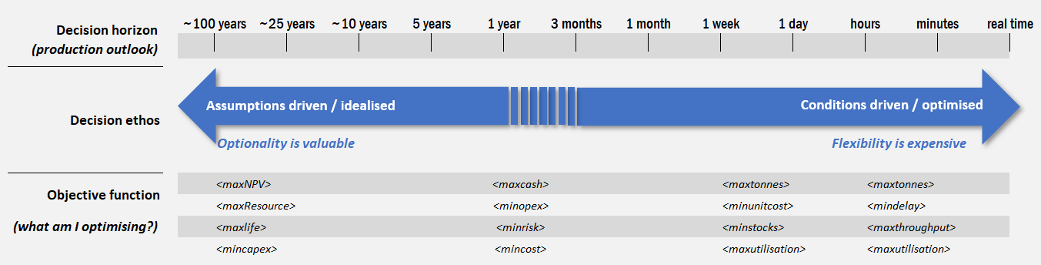

Value is discerned in the planning process by making the best choices and trade-offs between the real-world situation (which is described as conditions driven) and the longer-term business and investment case (which tends to be assumptions driven).

Value identification is useful, but in the wash-up, it is value capture that matters. Value is delivered through effective implementation of the plan. But plans carry extraction and delivery risk which, even if acknowledged, is not usually quantified in absolute value terms (“What is the risk-adjusted value of your annual operating plan?”). Stochastic analysis shows us how value is created in the conversion of a risked plan into a delivered result, but if value can be created through effective planning it can just as easily be forfeited when the process is not done or executed well.

The classic concept of optimisation is about finding the mathematically ideal solution to an objective function against a range of both complementary and competing factors. This approach has been applied to strategic mine planning since the 1960’s and continues to be the gold standard. This is the assumptions-driven realm of mine planning, and it has tended to drive a deterministic approach to planning at shorter intervals. We call this “idealisation” to reflect the idealised nature of the planning context.

We touched on sports earlier. Another lesson planners can learn from elite sports is how athletes often have no choice but to train and compete with injury. The option of performing injury-free cannot be relied upon, which is why athletes have sports medicine, physiotherapy, bandages and strapping, painkillers, whatever it takes, to get on the field. If we look at mine planning and operations through this lens, we move into the realm of the successful team.

In other words, despite all the shortcomings and setbacks of our planning processes (our “injuries”), teams still need to perform and deliver value. Optimisation tools are here for this purpose – to help you push through those injuries and barriers to deliver the best performance on the field. This is the definition of success.

The new and present reality is that we can now apply optimisation techniques to short-term and near-real time planning and decision support. We can respond intelligently and quickly to real-world conditions and test our actions against medium, long-term and strategic planning horizons. This is real-world optimisation, and it is the key to successful teams.

About the author

Rod Smith is the founding Principal of Beresford Advisory, a Brisbane-based resources sector consultancy focussed on supporting better decision making across the mineral value chain. He is a fellow of the Australian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy and a mining leader who was a part of Rio Tinto for over 30 years. During that time he held a variety of technical, operating and leadership roles, most recently as Chief Advisor of Planning & Scheduling. In that role he developed Rio Tinto’s Orebody Productivity framework and established its Operations Research & Decision Science group, building internal and external partnerships in the field of Industrial Mathematics to unlock significant value for the group.

To contact Rod Smith please email: rod@beresfordadvisory.com